How to analyze an artwork: a step-by-step guide

This article has been written for high school art students who are working upon a critical study of art, sketchbook annotation or an essay-based artist study. It contains a list of questions to guide students through the process of analyzing visual material of any kind, including drawing, painting, mixed media, graphic design, sculpture, printmaking, architecture, photography, textiles, fashion and so on (the word ‘artwork’ in this article is all-encompassing). The questions include a wide range of specialist art terms, prompting students to use subject-specific vocabulary in their responses. It combines advice from art analysis textbooks as well as from high school art teachers who have first-hand experience teaching these concepts to students.

COPYRIGHT NOTE: This material is available as a printable art analysis PDF handout. This may be used free of charge in a classroom situation. To share this material with others, please use the social media buttons at the bottom of this page. Copying, sharing, uploading or distributing this article (or the PDF) in any other way is not permitted.

Why do we study art?

Almost all high school art students carry out critical analysis of artist work, in conjunction with creating practical work. Looking critically at the work of others allows students to understand compositional devices and then explore these in their own art. This is one of the best ways for students to learn.

Instructors who assign formal analyses want you to look—and look carefully. Think of the object as a series of decisions that an artist made. Your job is to figure out and describe, explain, and interpret those decisions and why the artist may have made them.

– The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 10

Art analysis tips

- ‘I like this’ or ‘I don’t like this’ without any further explanation or justification is not analysis. Personal opinions must be supported with explanation, evidence or justification.

- ‘Analysis of artwork’ does not mean ‘description of artwork’. To gain high marks, students must move beyond stating the obvious and add perceptive, personal insight. Students should demonstrate higher order thinking – the ability to analyse, evaluate and synthesize information and ideas. For example, if color has been used to create strong contrasts in certain areas of an artwork, students might follow this observation with a thoughtful assumption about why this is the case – perhaps a deliberate attempt by the artist to draw attention to a focal point, helping to convey thematic ideas.

Although description is an important part of a formal analysis, description is not enough on its own. You must introduce and contextualize your descriptions of the formal elements of the work so the reader understands how each element influences the work’s overall effect on the viewer.

– Sylvan Barnet, A Short Guide to Writing About Art 2

- Cover a range of different visual elements and design principles. It is common for students to become experts at writing about one or two elements of composition, while neglecting everything else – for example, only focusing upon the use of color in every artwork studied. This results in a narrow, repetitive and incomplete analysis of the artwork. Students should ensure that they cover a wide range of art elements and design principles, as well as address context and meaning, where required. The questions below are designed to ensure that students cover a broad range of relevant topics within their analysis.

- Write alongside the artwork discussed. In almost all cases, written analysis should be presented alongside the work discussed, so that it is clear which artwork comments refer to. This makes it easier for examiners to follow and evaluate the writing.

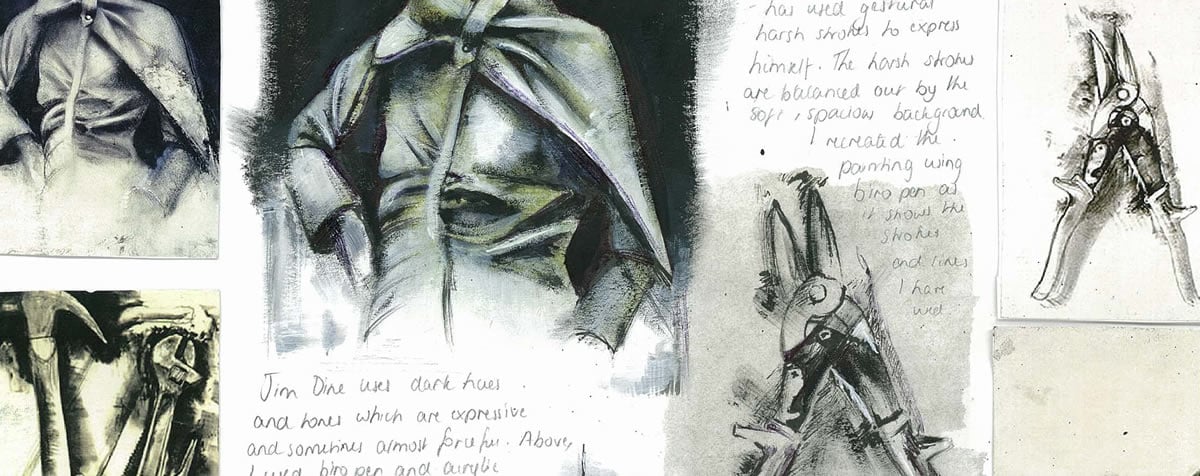

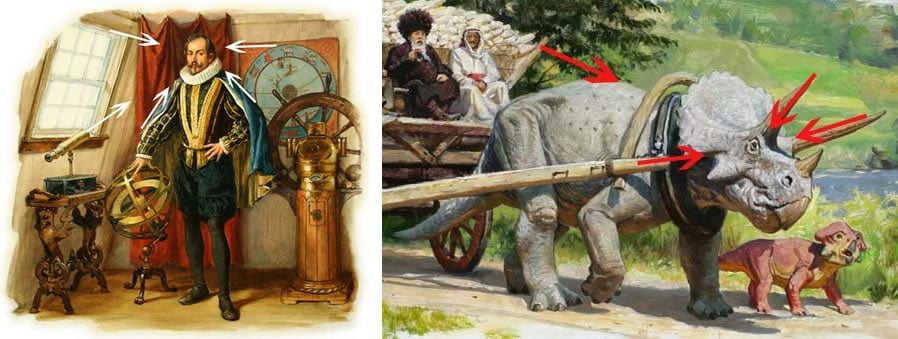

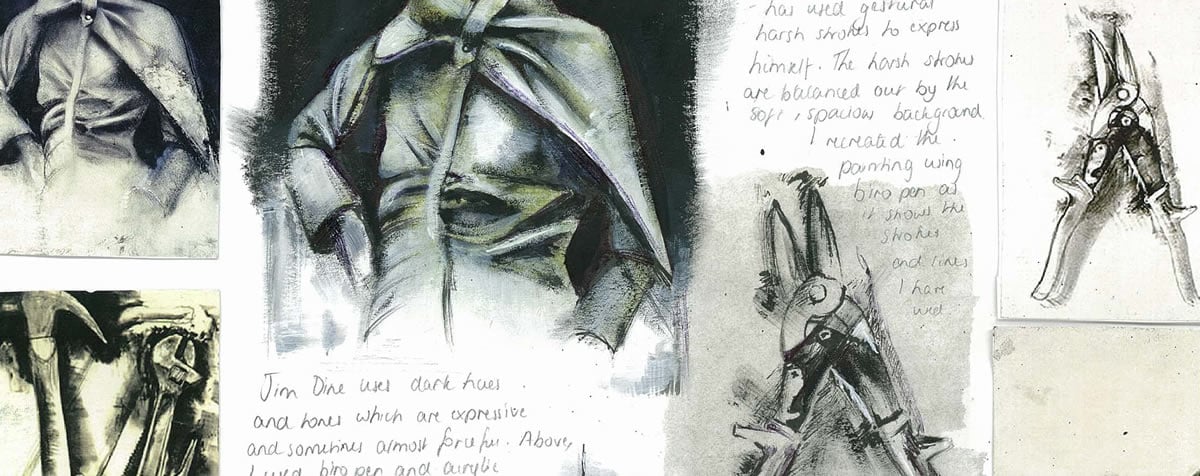

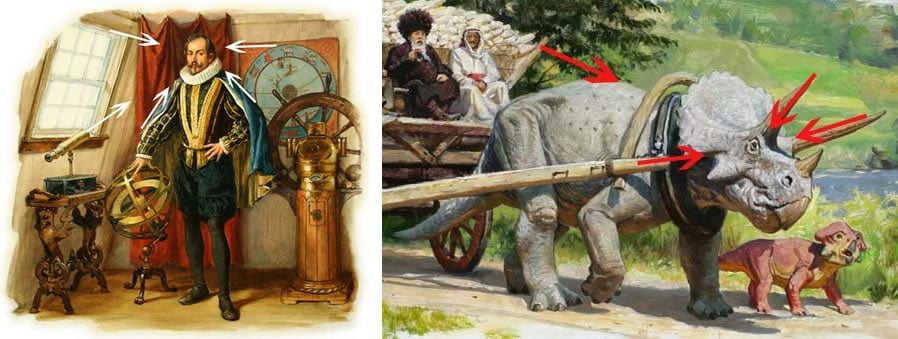

- Support writing with visual analysis. It is almost always helpful for high school students to support written material with sketches, drawings and diagrams that help the student understand and analyse the piece of art. This might include composition sketches; diagrams showing the primary structure of an artwork; detailed enlargements of small sections; experiments imitating use of media or technique; or illustrations overlaid with arrows showing leading lines and so on. Visual investigation of this sort plays an important role in many artist studies.

Making sketches or drawings from works of art is the traditional, centuries-old way that artists have learned from each other. In doing this, you will engage with a work and an artist’s approach even if you previously knew nothing about it. If possible do this whenever you can, not from a postcard, the internet or a picture in a book, but from the actual work itself. This is useful because it forces you to look closely at the work and to consider elements you might not have noticed before.

– Susie Hodge, How to Look at Art 7

Finally, when writing about art, students should communicate with clarity; demonstrate subject-specific knowledge; use correct terminology; generate personal responses; and reference all content and ideas sourced from others. This is explained in more detail in our article about high school sketchbooks.

What should students write about?

Although each aspect of composition is treated separately in the questions below, students should consider the relationship between visual elements (line, shape, form, value/tone, color/hue, texture/surface, space) and how these interact to form design principles (such as unity, variety, emphasis, dominance, balance, symmetry, harmony, movement, contrast, rhythm, pattern, scale, proportion) to communicate meaning.

As complex as works of art typically are, there are really only three general categories of statements one can make about them. A statement addresses form, content or context (or their various interrelations).

– Dr. Robert J. Belton, Art History: A Preliminary Handbook, The University of British Columbia 5

…a formal analysis – the result of looking closely – is an analysis of the form that the artist produces; that is, an analysis of the work of art, which is made up of such things as line, shape, color, texture, mass, composition. These things give the stone or canvas its form, its expression, its content, its meaning.

– Sylvan Barnet, A Short Guide to Writing About Art 2

This video by Dr. Beth Harris, Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Naraelle Hohensee provides an excellent example of how to analyse a piece of art (it is important to note that this video is an example of ‘formal analysis’ and doesn’t include contextual analysis, which is also required by many high school art examination boards, in addition to the formal analysis illustrated here):

Composition analysis: a list of questions

The questions below are designed to facilitate direct engagement with an artwork and to encourage a breadth and depth of understanding of the artwork studied. They are intended to prompt higher order thinking and to help students arrive at well-reasoned analysis.

It is not expected that students answer every question (doing so would result in responses that are excessively long, repetitious or formulaic); rather, students should focus upon areas that are most helpful and relevant for the artwork studied (for example, some questions are appropriate for analyzing a painting, but not a sculpture). The words provided as examples are intended to help students think about appropriate vocabulary to use when discussing a particular topic. Definitions of more complex words have been provided.

Students should not attempt to copy out questions and then answer them; rather the questions should be considered a starting point for writing bullet pointed annotation or sentences in paragraph form.

CONTENT, CONTEXT AND MEANING

Subject matter / themes / issues / narratives / stories / ideas

There can be different, competing, and contradictory interpretations of the same artwork.

An artwork is not necessarily about what the artist wanted it to be about.

– Terry Barrett, Criticizing Art: Understanding the Contemporary 6

Our interest in the painting grows only when we forget its title and take an interest in the things that it does not mention…”

– Françoise Barbe-Gall, How to Look at a Painting 8

- Does the artwork fall within an established genre (i.e. historical; mythical; religious; portraiture; landscape; still life; fantasy; architectural)?

- Are there any recognisable objects, places or scenes? How are these presented (i.e. idealized; realistic; indistinct; hidden; distorted; exaggerated; stylized; reflected; reduced to simplified/minimalist form; primitive; abstracted; concealed; suggested; blurred or focused)?

- Have people been included? What can we tell about them (i.e. identity; age; attire; profession; cultural connections; health; family relationships; wealth; mood/expression)? What can we learn from their pose (i.e. frontal; profile; partly turned; body language)? Where are they looking (i.e. direct eye contact with viewer; downcast; interested in other subjects within the artwork)? Can we work out relationships between figures from the way they are posed?

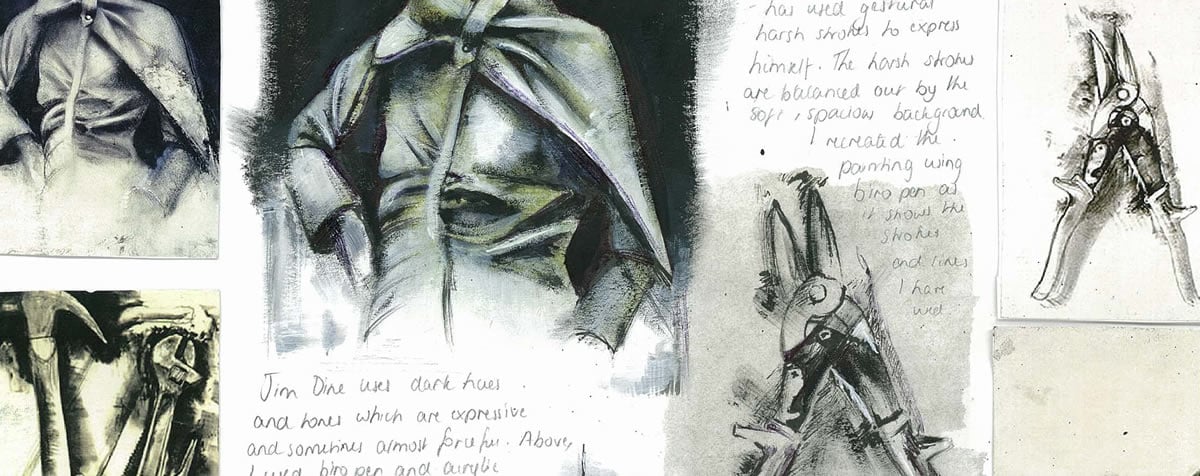

What do the clothing, furnishings, accessories (horses, swords, dogs, clocks, business ledgers and so forth), background, angle of the head or posture of the head and body, direction of the gaze, and facial expression contribute to our sense of the figure’s social identity (monarch, clergyman, trophy wife) and personality (intense, cool, inviting)?

– Sylvan Barnet, A Short Guide to Writing About Art 2

- What props and important details are included (drapery; costumes; adornment; architectural elements; emblems; logos; motifs)? How do aspects of setting support the primary subject? What is the effect of including these items within the arrangement (visual unity; connections between different parts of the artwork; directs attention; surprise; variety and visual interest; separates / divides / borders; transformation from one object to another; unexpected juxtaposition)?

If a waiter served you a whole fish and a scoop of chocolate ice cream on the same plate, your surprise might be caused by the juxtaposition, or the side-by-side contrast, of the two foods.

– Vocabulary.com

A motif is an element in a composition or design that can be used repeatedly for decorative, structural, or iconographic purposes. A motif can be representational or abstract, and it can be endowed with symbolic meaning. Motifs can be repeated in multiple artworks and often recur throughout the life’s work of an individual artist.

– John A. Parks, Universal Principles of Art 11

- Does the artwork communicate an action, narrative or story (i.e. historical event or illustrate a scene from a story)? Has the arrangement been embellished, set up or contrived?

- Does the artwork explore movement? Do you gain a sense that parts of the artwork are about to change, topple or fall (i.e. tension; suspense)? Does the artwork capture objects in motion (i.e. multiple or sequential images; blurred edges; scene frozen mid-action; live performance art; video art; kinetic art)?

- What kind of abstract elements are shown (i.e. bars; shapes; splashes; lines)? Have these been derived from or inspired by realistic forms? Are they the result of spontaneous, accidental creation or careful, deliberate arrangement?

- Does the work include the appropriation of work by other artists, such as within a parody or pop art? What effect does this have (i.e. copyright concerns)?

Parody: mimicking the appearance and/or manner of something or someone, but with a twist for comic effect or critical comment, as in Saturday Night Live’s political satires

– Dr. Robert J. Belton, Art History: A Preliminary Handbook, The University of British Columbia 5

- Does the subject captivate an instinctual response, such as items that are informative, shocking or threatening for humans (i.e. dangerous places; abnormally positioned items; human faces; the gaze of people; motion; text)? Heap map tracking has demonstrated that these elements catch our attention, regardless of where they are positioned – James Gurney writes more about this fascinating topic.

- What kind of text has been used (i.e. font size; font weight; font family; stenciled; hand-drawn; computer-generated; printed)? What has influenced this choice of text?

- Do key objects or images have symbolic value or provide a cue to meaning? How does the artwork convey deeper, conceptual themes (i.e. allegory; iconographic elements; signs; metaphor; irony)?

Allegory is a device whereby abstract ideas can be communicated using images of the concrete world. Elements, whether figures or objects, in a painting or sculpture are endowed with symbolic meaning. Their relationships and interactions combine to create more complex meanings.

– John A. Parks, Universal Principles of Art 11

An iconography is a particular range or system of types of image used by an artist or artists to convey particular meanings. For example in Christian religious painting there is an iconography of images such as the lamb which represents Christ, or the dove which represents the Holy Spirit.

– Tate.org.uk

- What tone of voice does the artwork have (i.e. deliberate; honest; autobiographical; obvious; direct; unflinching; confronting; subtle; ambiguous; uncertain; satirical; propagandistic)?

- What is your emotional response to the artwork? What is the overall mood (i.e positive; energetic; excitement; serious; sedate; peaceful; calm; melancholic; tense; uneasy; uplifting; foreboding; calm; turbulent)? Which subject matter choices help to communicate this mood (i.e. weather and lighting conditions; color of objects and scenes)?

- Does the title change the way you interpret the work?

- Were there any design constraints relating to the subject matter or theme/s (i.e. a sculpture commissioned to represent a specific subject, place or idea)?

- Are there thematic connections with your own project? What can you learn from the way the artist has approached this subject?

Wider contexts

All art is in part about the world in which it emerged.

– Terry Barrett, Criticizing Art: Understanding the Contemporary 6

- Supported by research, can you identify when, where and why the work was created and its original intention or purpose (i.e. private sale; commissioned for a specific owner; commemorative; educational; promotional; illustrative; decorative; confrontational; useful or practical utility; communication; created in response to a design brief; private viewing; public viewing)? In what way has this background influenced the outcome (i.e. availability of tools, materials or time; expectations of the patron / audience)?

- Where is the place of construction or design site and how does this influence the artwork (i.e. reflects local traditions, craftsmanship, or customs; complements surrounding designs; designed to accommodate weather conditions / climate; built on historic site)? Was the artwork originally located somewhere different?

- Which events and surrounding environments have influenced this work (i.e. natural events; social movements such as feminism; political events, economic situations, historic events, religious settings, cultural events)? What effect did these have?

- Is the work characteristic of an artistic style, movement or time period? Has it been influenced by trends, fashions or ideologies? How can you tell?

- Can you make any relevant connections or comparisons with other artworks? Have other artists explored a similar subject in a similar way? Did this occur before or after this artwork was created?

- Can you make any relevant connections to other fields of study or expression (i.e. geography, mathematics, literature, film, music, history or science)?

- Which key biographical details about the artist are relevant in understanding this artwork (upbringing and personal situation; family and relationships; psychological state; health and fitness; socioeconomic status; employment; ethnicity; culture; gender; education, religion; interests, attitudes, values and beliefs)?

- Is this artwork part of a larger body of work? Is this typical of the work the artist is known for?

- How might your own upbringing, beliefs and biases distort your interpretation of the artwork? Does your own response differ from the public response, that of the original audience and/or interpretation by critics?

- How do these wider contexts compare to the contexts surrounding your own work?

COMPOSITION AND FORMAT

Format

- What is the overall size, shape and orientation of the artwork (i.e. vertical, horizontal, portrait, landscape or square)? Has this format been influenced by practical considerations (i.e. availability of materials; display constraints; design brief restrictions; screen sizes; common aspect ratios in film or photography such as 4:3 or 2:3; or paper sizes such as A4, A3, A2, A1)?

- How do images fit within the frame (cropped; truncated; shown in full)? Why is this format appropriate for the subject matter?

- Are different parts of the artwork physically separate, such as within a diptych or triptych?

- Where are the boundaries of the artwork (i.e. is the artwork self-contained; compact; intersecting; sprawling)?

- Is the artwork site-specific or designed to be displayed across multiple locations or environments?

- Does the artwork have a fixed, permanent format, or was it modified, moved or adjusted over time? What causes such changes (i.e. weather and exposure to the elements – melting, erosion, discoloration, decaying, wind movement, surface abrasion; structural failure – cracking, breaking; damage caused by unpredictable events, such as fire or vandalism; intentional movement, such as rotation or sensor response; intentional impermanence, such as an installation assembled for an exhibition and removed afterwards; viewer interaction; additions, renovations and restoration by subsequent artists or users; a project so expansive it takes years to construct)? How does this change affect the artwork? Are there stylistic variances between parts?

- Is the artwork viewed from one angle or position, or are dynamic viewpoints and serial vision involved? (Read more about Gordon Cullen’s concept of serial vision here).

- How does the scale and format of the artwork relate to the environment where it is positioned, used, installed or hung (i.e. harmonious with landscape typography; sensitive to adjacent structures; imposing or dwarfed by surroundings; human scale)? Is the artwork designed to be viewed from one vantage point (i.e. front facing; viewed from below; approached from a main entrance; set at human eye level) or many? Are images taken from the best angle?

- Would a similar format benefit your own project? Why / why not?

Structure / layout

- Has the artwork been organised using a formal system of arrangement or mathematical proportion (i.e. rule of thirds; golden ratio or spiral; grid format; geometric; dominant triangle; or circular composition) or is the arrangement less predictable (i.e. chaotic, random, accidental, fragmented, meandering, scattered; irregular or spontaneous)? How does this system of arrangement help with the communication of ideas? Can you draw a diagram to show the basic structure of the artwork?

- Can you see a clear intention with alignment and positioning of parts within the artwork (i.e. edges aligned; items spaced equally; simple or complex arrangement; overlapping, clustered or concentrated objects; dispersed, separate items; repetition of forms; items extending beyond the frame; frames within frames; bordered perimeter or patterned edging; broken borders)? What effect do these visual devices have (i.e. imply hierarchy; help the viewer understand relationships between parts of artwork; create rhythm)?

- Does the artwork have a primary axis of symmetry (vertical, diagonal, horizontal)? Can you locate a center of balance? Is the artwork symmetrical, asymmetrical (i.e. stable), radial, or intentionally unbalanced (i.e. to create tension or unease)?

- Can you draw a diagram to illustrate emphasis and dominance (i.e. ‘blocking in’ mass, where the ‘heavier’ dominant forms appear in the composition)? Where are dominant items located within the frame?

- How do your eyes move through the composition?

- Could your own artwork use a similar organisational structure?

Line

- What types of linear mark-making are shown (thick; thin; short; long; soft; bold; delicate; feathery; indistinct; faint; irregular; intermittent; freehand; ruled; mechanical; expressive; loose; blurred; dashing; cross-hatching; meandering; gestural, fluid; flowing; jagged; spiky; sharp)? What atmosphere, moods, emotions or ideas do these evoke?

- Are there any interrupted, suggested or implied lines (i.e. lines that can’t literally be seen, but the viewer’s brain connects the dots between separate elements)?

- Where are the dominating lines in the composition and what is the effect of these? Can you overlay tracing paper upon an artwork to illustrate some of the important lines?

- Repeating lines: may simulate material qualities, texture, pattern or rhythm;

- Boundary lines: may segment, divide or separate different areas;

- Leading lines: may manipulate the viewer’s gaze, directing vision or lead the eye to focal points (eye tracking studies indicate that our eyes leap from one point of interest to another, rather than move smoothly or predictably along leading lines 9 . Lines may nonetheless help to establish emphasis by ‘pointing’ towards certain items);

- Parallel lines: may create a sense of depth or movement through space within a landscape;

- Horizontal lines: may create a sense of stability and permanence;

- Vertical lines: may suggest height, reaching upwards or falling;

- Intersecting perpendicular lines: may suggest rigidity, strength;

- Abstract lines: may balance the composition, create contrast or emphasis;

- Angular / diagonal lines: may suggest tension or unease;

- Chaotic lines: may suggest a sense of agitation or panic;

- Underdrawing, construction lines or contour lines: describe form (learn more about contour lines in our article about line drawing);

- Curving / organic lines: may suggest nature, peace, movement or energy.

- What is the relationship between line and three-dimensional form? Are outlines used to define form and edges?

- Would it be appropriate to use line in a similar way within your own artwork?

Shape and form

- Can you identify a dominant visual language within the shapes and forms shown (i.e. geometric; angular; rectilinear; curvilinear; organic; natural; fragmented; distorted; free-flowing; varied; irregular; complex; minimal)? Why is this visual language appropriate?

- How are the edges of forms treated (i.e. do they fade away or blur at the edges, as if melting into the page; ripped or torn; distinct and hard-edged; or, in the words of James Gurney, 9 do they ‘dissolve into sketchy lines, paint strokes or drips’)?

- Are there any three-dimensional forms or relief elements within the artwork, such as carved pieces, protruding or sculptural elements? How does this affect the viewing of the work from different angles?

- Is there a variety or repetition of shapes/forms? What effect does this have (i.e. repetition may reinforce ideas, balance composition and/or create harmony / visual unity; variety may create visual interest or overwhelm the viewer with chaos)?

- How are shapes organised in relation to each other, or with the frame of the artwork (i.e. grouped; overlapping; repeated; echoed; fused edges; touching at tangents; contrasts in scale or size; distracting or awkward junctions)?

- Are silhouettes (external edges of objects) considered?

All shapes have silhouettes, and vision research has shown that one of the first tasks of perception is to be able to sort out the silhouette shapes of each of the elements in a scene.

– James Gurney, Imaginative Realism 9

- Are forms designed with ergonomics and human scale in mind?

Ergonomics: an applied science concerned with designing and arranging things people use so that the people and things interact most efficiently and safely

– Merriam-webster.com

- Can you identify which forms are functional or structural, versus ornamental or decorative?

- Have any forms been disassembled, ‘cut away’ or exposed, such as a sectional drawing? What is the purpose of this (i.e. to explain construction methods; communicate information; dramatic effect)?

- Would it be appropriate to use shape and form in a similar way within your own artwork?

Value / tone / light

- Has a wide tonal range been used in the artwork (i.e. a broad range of darks, highlights and mid-tones) or is the tonal range limited (i.e. pale and faint; subdued; dull; brooding and dark overall; strong highlights and shadows, with little mid-tone values)? What is the effect of this?

- Where are the light sources within the artwork or scene? Is there a single consistent light source or multiple sources of light (sunshine; light bulbs; torches; lamps; luminous surfaces)? What is the effect of these choices (i.e. mimics natural lighting conditions at a certain time of day or night; figures lit from the side to clarify form; contrasting background or spot-lighting used to accentuate a focal area; soft and diffused lighting used to mute contrasts and minimize harsh shadows; dappled lighting to signal sunshine broken by surrounding leaves; chiaroscuro used to exaggerate theatrical drama and impact; areas cloaked in darkness to minimize visual complexity; to enhance our understanding of narrative, mood or meaning)?

One of the most important ways in which artists can use light to achieve particular effects is in making strong contrasts between light and dark. This contrast is often described as chiaroscuro.

– Matthew Treherne, Analysing Paintings, University of Leeds 3

- Are representations of three-dimensional objects and figures flat or tonallymodeled? How do different tonal values change from one to the next (i.e. gentle, smooth gradations; abrupt tonal bands)?

- Are there any unusual, reflective or transparent surfaces, mediums or materials which reflect or transmit light in a special way?

- Has tone been used to help communicate atmospheric perspective (i.e. paler and bluer as objects get further away)?

- Are gallery or environmental light sources where the artwork is displayed fixed or fluctuating? Does the work appear different when viewed at different times of day? How does this affect your interpretation of the work?

- Are shadows depicted within the artwork? What is the effect of these shadows (i.e. anchors objects to the page; creates the illusion of depth and space; creates dramatic contrasts)?

- Do sculptural protrusions or relief elements catch the light and/or create cast shadows or pockets of shadow upon the artwork? How does this influence the viewer’s experience?

- How has tone been used to help direct the viewer’s attention to focal areas?

- Would it be appropriate to use value / tone in a similar way within your own artwork? Why / why not?

Color / hue

- Can you view the true color of the artwork (i.e. are you viewing a low-quality reproduction or examining the artwork in poor lighting)?

- Which color schemes have been used within the artwork (i.e. harmonious; complementary; primary; monochrome; earthy; warm; cool/cold)? Has the artist used a broad or limited color palette (i.e. variety or unity)? Which colors dominate?

- How would you describe the intensity of the colors (vibrant; bright; vivid; glowing; pure; saturated; strong; dull; muted; pale; subdued; bleached; diluted)?

- Are colors transparent or opaque? Can you see reflected color?

- Has color contrast been used within the artwork (i.e. extreme contrasts; juxtaposition of complementary colors; garish / clashing / jarring)? Are there any abrupt color changes or unexpected uses of color?

- What is the effect of these color choices (i.e. expressing symbolic or thematic ideas; descriptive or realistic depiction of local color; emphasizing focal areas; creating the illusion of aerial perspective; relationships with colors in surrounding environment; creating balance; creating rhythm/pattern/repetition; unity and variety within the artwork; lack of color places emphasis upon shape, detail and form)? What kind of atmosphere do these colors create?

It is often said that warm colors (red, orange, yellow) come forward and produce a sense of excitement (yellow is said to suggest warmth and happiness, as in the smiley face), whereas cool colors (blue, green) recede and have a calming effect. Experiments, however, have proved inconclusive; the response to color – despite clichés about seeing red or feeling blue – is highly personal, highly cultural, highly varied.

– Sylvan Barnet, A Short Guide to Writing About Art 2

- Would it be appropriate to use color in a similar way within your own artwork?

Texture / surface / pattern

- Are there any interesting textural, tactile or surface qualities within the artwork (i.e. bumpy; grooved; indented; scratched; stressed; rough; smooth; shiny; varnished; glassy; glossy; polished; matte; sandy; grainy; gritted; leathery; spiky; silky)? How are these created (i.e. inherent qualities of materials; impasto mediums; sculptural materials; illusions or implied texture, such as cross-hatching; finely detailed and intricate areas; organic patterns such as foliage or small stones; repeating patterns; ornamentation)?

- How are textural or patterned elements positioned and what effect does this have (i.e. used intermittently to provide variety; repeating pattern creates rhythm; patterns broken create focal points; textured areas create visual links and unity between separate areas of the artwork; balance between detailed/textured areas and simpler areas; glossy surface creates a sense of luxury; imitation of texture conveys information about a subject, i.e. softness of fur or strands of hair)?

- Would it be appropriate to use texture / surface in a similar way within your own artwork?

Space

Industrial and architectural landscapes are particularly concerned with the arrangement of geometries and form in space…

Dr. Ben Guy, Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment using CGI Digital Twins, Urban CGI 12

- Is the pictorial space shallow or deep? How does the artwork create the illusion of depth (i.e. layering of foreground, middle-ground, background; overlapping of objects; use of shadows to anchor objects; positioning of items in relationship to the horizon line; linear perspective (learn more about one point perspective here); tonal modeling; relationships with adjacent objects and those in close proximity – including the human form – to create a sense of scale; spatial distortions or optical illusions; manipulating scale of objects to create ‘surrealist’ spaces where true scale is unknown)?

- Has an unusual viewpoint been used (i.e. worm’s view; aerial view, looking out a window or through a doorway; a scene reflected in a mirror or shiny surface; looking through leaves; multiple viewpoints combined)? What is the effect of this viewpoint (i.e. allows certain parts of the scene to be dominant and overpowering or squashed, condensed and foreshortened; or suggests a narrative between two separate spaces; provides more information about a space than would normally be seen)?

- Is the emphasis upon mass or void? How densely arranged are components within the artwork or picture plane? What is the relationship between object and surrounding space (i.e. compact / crowded / busy / densely populated, with little surrounding space; spacious; careful interplay between positive and negative space; objects clustered to create areas of visual interest)? What is the effect of this (i.e. creates a sense of emptiness or isolation; business / visual clutter creates a feeling of chaos or claustrophobia)?

- How does the artwork engage with real space – in and around the artwork (i.e. self-contained; closed off; eye contact with viewer; reaching outwards)? Is the viewer expected to move through the artwork? What is the relationship between interior and exterior space? What connections or contrasts occur between inside and out? Is it comprised of a series of separate or linked spaces?

- Would it be appropriate to use space in a similar way within your own artwork?

Use of media / materials

- What materials and mediums has the artwork been constructed from? Have materials been concealed or presented deceptively (i.e. is there an authenticity / honesty of materials; are materials celebrated; is the structure visible or exposed)? Why were these mediums selected (weight; color; texture; size; strength; flexibility; pliability; fragility; ease of use; cost; cultural significance; durability; availability; accessibility)? Would other mediums have been appropriate?

- Which skills, techniques, methods and processes were used (i.e. traditional; conventional; industrial; contemporary; innovative)? It is important to note that the examiners do not want the regurgitation of long, technical processes, but rather to see personal observations about how processes effect and influence the artwork in question. Would replicating part of the artwork help you gain a better understanding of the processes used?

- Has the artwork been built in layers or stages? For example:

- Painting: gesso ground > textured mediums > underdrawing > blocking in colors > defining form > final details;

- Architecture: brief > concepts > development > working drawings > foundations > structure > cladding > finishes;

- Graphic design: brief > concepts > development > Photoshop > proofing > printing.

Finally, remember that these questions are a guide only and are intended to make you start to think critically about the art you are studying and creating.

Further Reading

If you enjoyed this article you may also like our article about high school sketchbooks (which includes a section about sketchbook annotation). If you are looking for more assistance with how to write an art analysis essay you may like our series about writing an artist study.

[1] A guide for Analyzing Works of Art; Sculpture and Painting, Durantas

[2] A Short Guide to Writing About Art, Sylvan Barnet (2014) (Amazon affiliate link)

[3] Analysing Paintings, Matthew Treherne, University of Leeds

[5] Art History: A Preliminary Handbook, Dr. Robert J. Belton, The University of British Columbia (1996)

[7] How to Look at Art, Susie Hodge (2015) (Amazon affiliate link)

[8] How to Look at a Painting, Françoise Barbe-Gall (2011) (Amazon affiliate link)

[10] Art History, The Writing Centre, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Amiria Gale

Amiria has been an Art & Design teacher and a Curriculum Co-ordinator for seven years, responsible for the course design and assessment of student work in two high-achieving Auckland schools. She has a Bachelor of Architectural Studies, Bachelor of Architecture (First Class Honours) and a Graduate Diploma of Teaching. Amiria is a CIE Accredited Art & Design Coursework Assessor.